The Holy Grail

The proverbial holy grail of neuroscience is to translate neural impulses into behavior and vice versa: cracking the neural code. It’s a research goal that holds not only a certain intellectual allure but also important clinical ramifications. Many neurological and psychiatric diseases, from dementia to depression, addiction, and CTE notoriously lack quantitative definitions or reliable biomarkers, meaning few current scanning methods, blood test, nasal swabs, or questionnaires can give doctors definitive disease prognoses or severity assessments in the way a pulmonologist can see a tumor in an CT-scan or a genetic screen can confirm Down’s syndrome. Both the biochemical mechanisms and signal processing capabilities of the brain need to be understood for the advancement of neurotherapeutics.

One of the biggest impediments contemporary neuroscientists face is a lack of tools to record from the animal brain in vivo . The problem is multifold. First, consider the scale: the adult human brain is thought to contain 85 billion neurons, each of which may fire an action potential that occurs over roughly 5 milliseconds. For a coarse analogy, imagine how hard of a task it would be to overhear a conversation between 10 times the number of people on Earth, at 80 times the speed of a normal conversation, trying to figure out what each person is saying (while they are speaking in different languages and at different volumes).

This gargantuan problem is partly alleviated by the fact that certain regions of the brain can be associated with specific functions across all subjects belonging to the same species, and there is redundancy in neural circuitry that ensures individual neurons are unlikely to be the sole transmitters of information in important pathways. The daunting task of deciphering how neurons communicate nevertheless requires careful experimentation on both animals and humans.

What of the connections between neurons in different parts of the brain? How does the brain decide to move one’s mouth in response to a planned word to utter, and how do we learn from memories and experiences that are sensed from practices, experiences, and emotions? To further complicate the matter, the recording apparatus can’t influence a subject’s behavior - a mouse with a large apparatus strapped onto its head will behave unnaturally, producing noisy or indecipherable neural firing as it attempts to adapt to the weight of the electrode or fears for its life. The ideal machine records the firing of every neuron as non-invasively and surreptitiously as possible.

If such a machine existed, scientists could present varying stimuli to record large-scale neural responses, and map responses to stimuli in different regions of the brain using computational methods. Ideally, such a mapping would reveal causal mechanisms in neural circuits: how a stimulus elicits behavior, and more specifically how that behavior is represented across the brain, over time. Imagine learning how to play the piano: your ears need to pick up diverse pitches of sound, your eyes may need to read music, and your fingers need to move. As you learn, reinforcement from hearing yourself play or even from other people builds your technical ability, and eventually you may even memorize some songs. A neuroscientist studying you may want to see how information from your cerebellum, retina, and cochlea flows to various parts of your brain while this happens, and how these networks may change over time as you gain experience. Unfortunately, this is akin to finding a needle in a haystack, because it is impossible to extract neural activity from the brain at such a spatiotemporal scale at present.

Before I started working in this field, I had the misdirected notion the problem of scaling neural recording was primarily one of insufficient algorithmic ingenuity - I mistakenly assumed that better computer vision models would be the answer to interpreting fMRI scans for automating diagnoses, or that more centrally collected, massive high-quality patient databases would reveal the mechanisms underlying certain diseases (these ideas are, I have been told, something of an existing stereotype in engineers’ thinking). While these are important endeavors that can have tangible clinical benefits, they are not holistic solutions for “modeling the brain”.

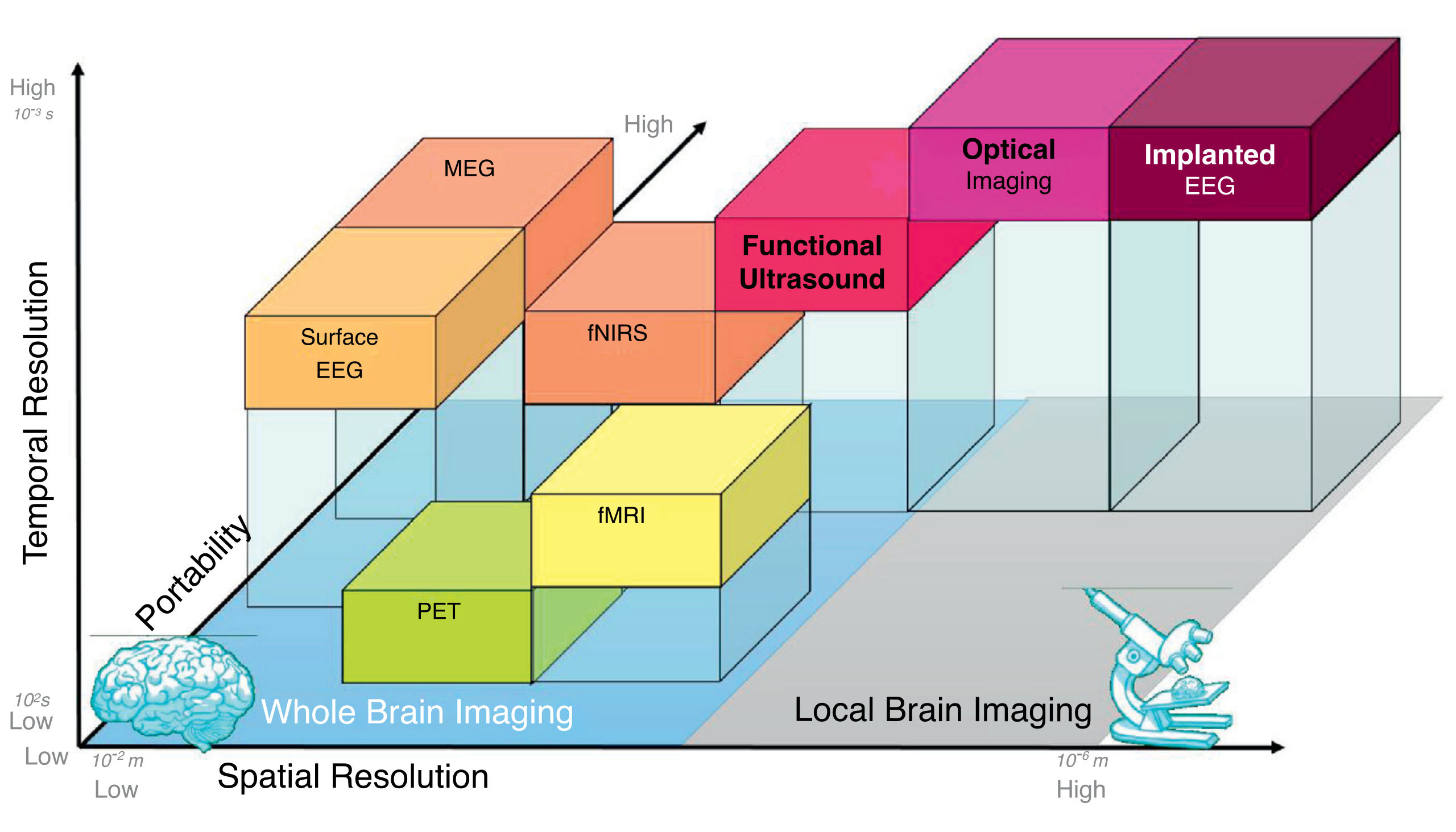

So the question remains: how do we learn anything about the brain, and what can we do to solve the puzzle of unraveling its code? Modern brain recording technologies make tradeoffs in spatial resolution, temporal resolution and invasiveness to give neuroscientists insights about brain activity. Now that I’ve understood this problem in a little more detail, I hope writing about data acquisition from the brain sheds some light on why understanding the brain is such a difficult task for others who are coming from an engineering background like me.

By Thomas Deffieux, Charlie Demene, Mathieu Pernot, Mickael Tanter - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.001, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90400311

By Thomas Deffieux, Charlie Demene, Mathieu Pernot, Mickael Tanter - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.001, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90400311

In this article I only mention modalities that help monitor activity in parts of the brain (if one were to ask, say, “How do the occipital cortex and hippocampus behave over a 20 second time period after you see a familiar face?”), which are commonly called “functional” imaging paradigms in clinical practice. I will leave out any discussion of “structural” imaging, which is concerned primarily with visualizing physical attributes of the brain at a given moment in time (asking, say “Where is there a tumor in the brain?”).

Electrophysiology

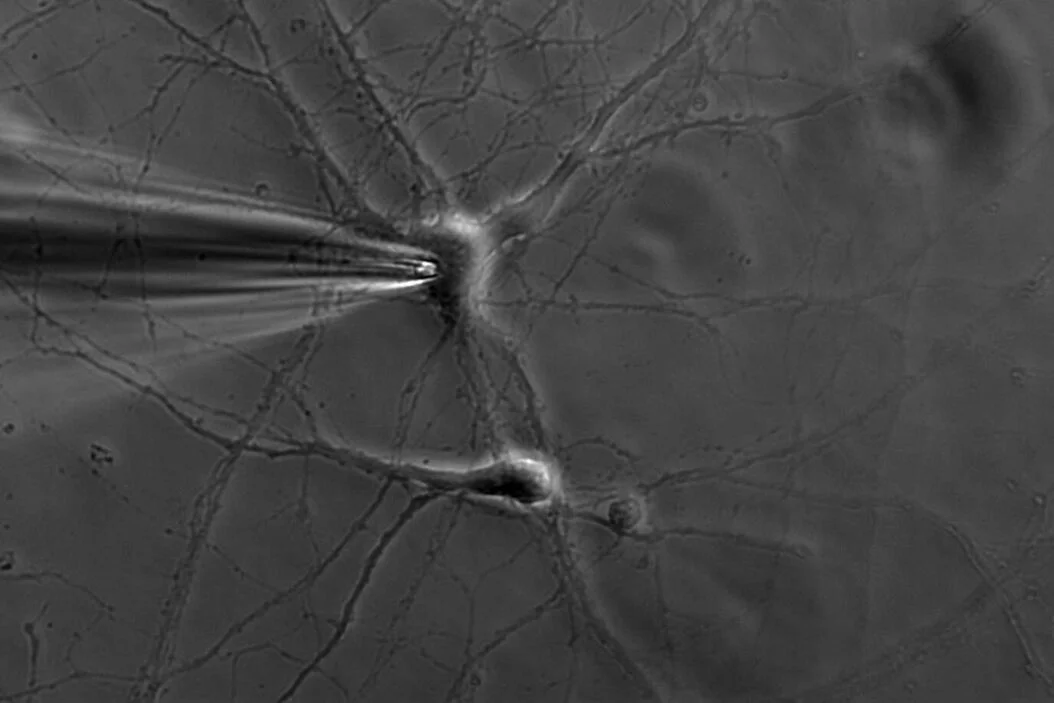

The most direct way of accessing information from populations of neurons is by directly measuring their electrical activity as a function of time. In a cell in a dish, one is able to directly poke a desired neuronal region to measure current passing through it, and in fact a very common technique called patch-clamping applies this basic principle. A similar idea can then be extended to living cells - record electrical activity of one or more neurons using an electrode. There are a couple ways to go about this, depending on the cells you intend to record and the invasiveness of the recording. It’s ideal to make direct contact with the target neurons to maximize signal over noise, as layers of other tissue, bone and/or skin may distort the signal. The drawback is that removing tissue effectively means performing a surgery, which might be risky or impair voluntary function. This constraint is the invasiveness of a recording method, and is an important consideration in an experimental or clinical setup.

Image source: https://www.leica-microsystems.com/science-lab/life-science/the-patch-clamp-technique/

Image source: https://www.leica-microsystems.com/science-lab/life-science/the-patch-clamp-technique/

My company Bionic Sight is working on a treatment for vision restoration, which means in part that we’re interested in recording the neurons of the retina and the neurons of the visual cortex in order to determine the behavior of these neurons with respect to treatment. The retinal electrophysiology recording is called an electroretinogram (ERG) and places electrodes on the cornea (surface) of the eye to measure the response of the retina to a given stimulus. An alternative, less invasive option is the electroencephalogram (EEG), which places electrodes directly on the scalp. For example, a common EEG procedure called the visually-evoked potential (VEP) tests the patient’s responses to flashes of light by placing electrodes near the back of their head. Similar tradeoffs between information and invasiveness are apparent in all neuroscientific studies.

For some applications like motor neuroprosthetics, you need less noisy, more population-specific measurements, at the brain level which involves placing electrodes on the cortical surface. This form of brain recording, interchangeably known as intracranial EEG (iEEG) or electrocorticography (ECG, not to be confused with an electrocardiogram), requires surgically removing part of the skull and implanting the electrode on the surface of the brain at a region of interest. Many well-known neuroprosthetic device companies like Neuralink, Precision Neuroscience, and Paradromics are using iEEGs and modifications of iEEGs to record neural populations in the motor cortex to map neural activity to patient intent in an activity like moving a computer mouse cursor. The recently achieved state-of-the art in this area is a 4,096 electrode implant created by Precision Neuroscience.

Electrophysiology techniques share some common drawbacks. First, there is the tradeoff between invasiveness and precision. To get a strong signal, as it stands, you need to perform a surgery. Next, they are localized, such that even iEEGs can only record several hundreds of neurons at a time in living humans, a needle in the haystack of 85 billion neurons we have. This doesn’t work when you want to know how different regions of the brain are involved in a particular process. These drawbacks motivate some of the other techniques neuroscientists use to understand neural activity.

Noninvasive Functional Imaging

While having access to behavior at the neuronal level is ideal, it is infeasible to to scale electrophysiology with the current technology available to understand relationships between parts of the brain or map the the activity of multiple neural circuits to a person’s behavior, because it would necessitate millions of electrodes possibly being placed deep into sub-cortical tissue. Instead, to study the brain’s behavior at a coarser scale, scientists opt to use functional imaging, which simply means imaging of the brain while the subject is performing a specific activity. These methods trade off the high spatial and temporal resolution of electrode-based recordings for the ability to noninvasively probe larger regions of interest in the brain.

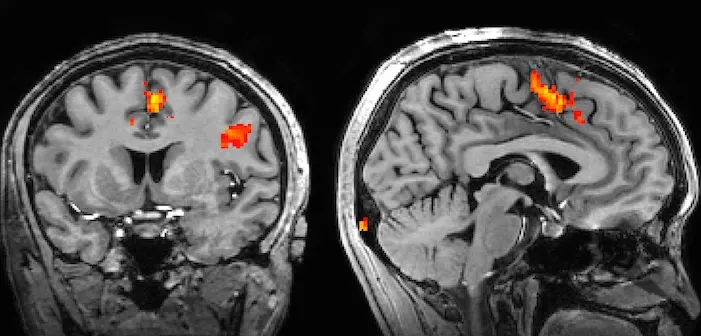

The most common functional imaging technique is functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), an adaptation of the traditional MRI used all over the body that is specific to the brain. fMRI takes advantage of the electromagnetic properties of blood to track blood flow in the brain over the course of an experiment, with the assumption that blood will rush to the parts of the brain that are most involved in a certain task (termed “hemodynamic response”). fMRI was the first functional imaging technique, developed by Seiji Ogawa, who showed that hemoglobin had different magnetic properties in its oxygenated and deoxygenated state, a difference termed the Blood-Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) contrast, which could be detected using MRI. One challenge with fMRI is the low sensitivity of the BOLD response- you need to be studying stimuli and/or subjects that generate a sufficient BOLD contrast over the noise. While a high signal-to-noise ratio is an obvious goal of any recording paradigm, noise can come from other brain processes or movements during the scan, and the hemodynamic response can vary between subjects. Furthermore, fMRI requires the subject to lie still in a large apparatus, which limits its experimental utility, and the apparatus can be distractingly loud for patients (quite literally a source of noise). fMRI has nonetheless been instrumental to advancing neuroscientists’ understanding of the regions of the brain and how they interact.

Image source: Image from https://www.ndcn.ox.ac.uk/divisions/fmrib/what-is-fmri/how-is-fmri-used

Image source: Image from https://www.ndcn.ox.ac.uk/divisions/fmrib/what-is-fmri/how-is-fmri-used

Radiation in non-visible wavelengths that are used in other parts of the body have been adapted to functional imaging in the brain as well. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) allows noninvasive measurement of hemodynamic response near the cortical surface by taking advantage of the absorption properties of hemoglobin to this form of radiation. fNIRS sensors have been decreasing in size and cost, making fNIRS a useful modality when subjects need to be allowed to move freely. Functional ultrasound (fUS) imaging is another promising technique that uses the Doppler effect to localize blood flow. fUS is gaining momentum for its possible clinical application because at high frequencies, it has high spatiotemporal resolution in a portable form factor. Crucially, these techniques all use properties of blood to detect changes in the brain, and vary in their spatiotemporal resolution, depth, and invasiveness.

However, all functional imaging techniques need to use blood flow as a proxy for neural activity. Magnetoencephalography (MEG), for example, records the magnetic fields created by the electric currents in the brain. The noise present in MEG varies depending on the source of neural activity and presents a higher temporal resolution than fMRI.

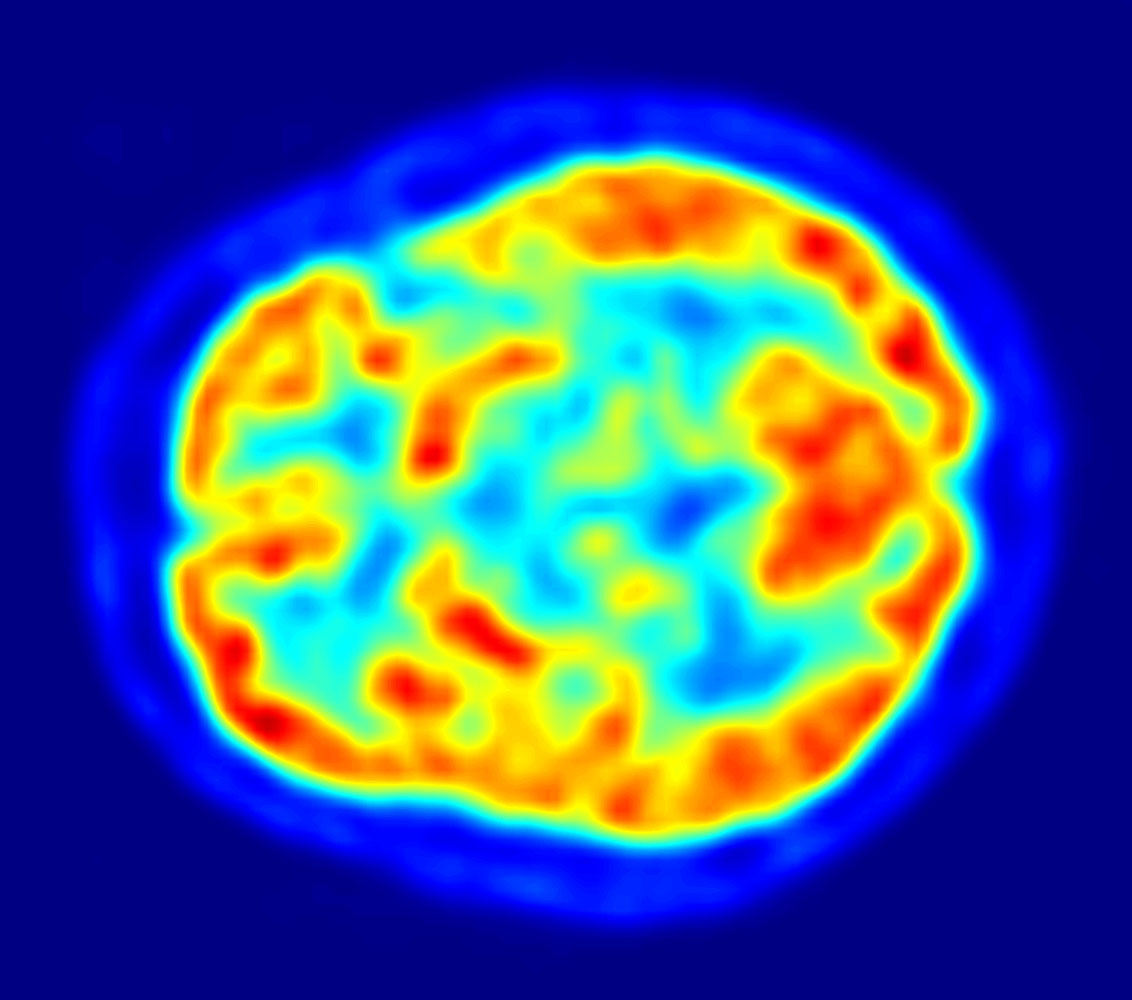

Yet another notable and common functional paradigm in use is positron emission tomography (PET). PET is a functional imaging paradigm used all over the body that introduces radioactive material known as radiotracers and tracks the reaction of the radiotracer at the site of interest. The materials of choice for the brain are oxygen-15, which is used to track to localize oxygenation, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which is used to localize glucose consumption. Drawbacks here are the requirement of radioactive material, which decays on the order of 2 to 30 minutes depending on the radiotracer, along with stationary and expensive tomography equipment. However, PETs are commonly used to study Alzheimer’s disease because Alzheimer’s has been observed to have an impact on both oxygen and glucose consumption.

Image source: Jens Maus via Wikimedia Commons)

Image source: Jens Maus via Wikimedia Commons)

Optical Imaging

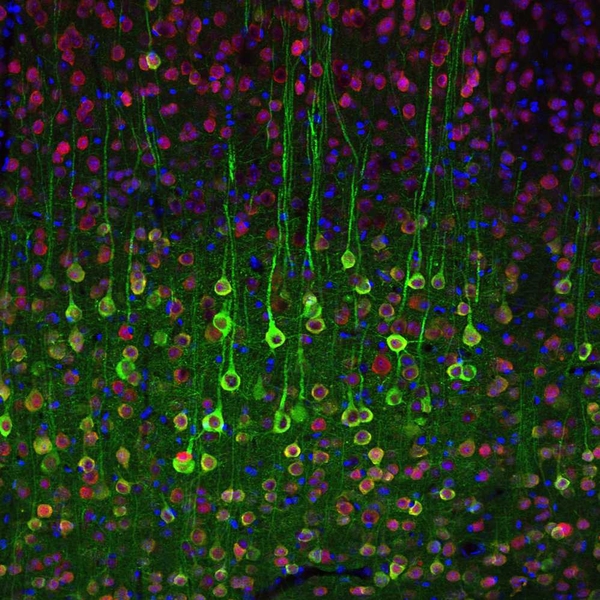

A last class of imaging tools uses microscopy to look at cellular activity. I had wrongly assumed that microscopy is reserved for slices of cell tissue, but it turns out types of microscopy can be used for observing neurons at single-cell resolution in living organisms, including primates. The technicalities of the different kinds of microscopy are beyond the scope of what I’m covering, but it suffices to say that techniques commonly used in other fields like fluorescence microscopy, light microscopy, and electron microscopy all have applications in neuroscience. For example, a particularly useful form of fluorescence microscopy is calcium imaging, a technique in which calcium indicators are introduced to the brain. This works because neural action potentials are marked by an influx of calcium. While the resolution of this is excellent, it is still invasive (a microscope needs to be inserted into the head) and requires the introduction of a fluorescent indicator. Furthermore, while having single-cell specific information is wonderful, the microscope can only focus on one part of the brain, so activity beyond a very specific region would not be recorded. Functional imaging and optical imaging therefore share some similar constraints.

Image source: MIT News, https://news.mit.edu/2012/neuron-imaging-calcium-1017

Image source: MIT News, https://news.mit.edu/2012/neuron-imaging-calcium-1017

The Right Choice

There isn’t necessarily a correct imaging modality even within a specific problem domain - some studies take fMRIs and PETs of subjects to have two ways of studying similar activity, and the choice of imaging modality comes down to the limitations and objectives of the experimental setup. The effort to crack the neural code will likely be a combination of several current methods and novel ones we come up with. The key constraints of spatiotemporal resolution and invasiveness, coupled with practical considerations of cost, availability, and study objectives, inform neuroscience researchers how to read brain activity.

What’s next? While the methods I detailed are still very much relevant in research, data acquisition to decode the human brain in its entirety may seem a distant reality. One area of neuroscience, connectomics, involves piecing together vast datasets of annotated microscopy images of model organisms to create a mapping of the brain: a recent milestone in connectomics celebrated the mapping of one cubic centimeter of mouse tissue. Other researchers are using technologies like fUS to both read and modulate brain activity in BMIs. Electrode based approaches are scaling capability exponentially akin to Moore’s Law, and the advancement of artificial intelligence is accelerating some of the painstaking parts of this process, but we don’t need to decode the brain in full to benefit patients. Excitingly, the academic results of the last decade are reaping clinical benefits now (including for Bionic Sight).