The project I worked on for the spring semester of my research with Cornell Data Science was a reimplementation of one of the famous results in reinforcement learning by a group at DeepMind (see paper). In the paper, the DeepMind group essentially trained a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to create successful policies for several Atari games with only image frames (256 x 256 RGB matrices of pixel values) as training inputs. This meant that the agent had no prior information about the dynamics of the game environment- no encoding of what a wall or a power-up was, for example. Furthermore, the DQN agents never tried to learn directly what these were; i.e. there was no convolutional network specifically to learn to find walls or power-ups. This type of RL-training is called “model-free” training because the policy it learns is independent of outside knowledge on the environment.

I chose Ms. Pac-Man because it one of the games not studied in the DeepMind paper. Ms. Pac-Man has added stochasticity as compared to (Mr.) Pac-Man because two of the ghosts, Blinky and Pinky, initiate each round with semi-random movement. For the purposes of this experiment, this is the most important difference. As a result of this stochasticity, a model-based agent that could find patterns in the ghosts’ movements in Pac-Man would fail to do so consistently in Ms. Pac-Man. The line of inquiry was therefore to see to what extent a DQN-based policy would learn to play this game, if at all, using the training methods of the DeepMind paper.

I won’t get into the details of the policy network architecture or image frame preprocessing, as those can be found in the paper linked previously. It suffices to say that the network architecture was not “fancy” (two convolutional layers followed by two fully-connected layers) and that the image frame preprocessing was similarly standard (grayscaling,resizing,cropping). Frames of images were stacked in the original paper because single frames often missed environment dynamics that were important- a single image frame does not show the ghosts’ movement or the player’s trajectory but several frames can capture these dynamics. The original paper also used frame-skipping for computational efficiency, meaning one frame of every two to four was used. These image stacks were then fed to the policy network, which was expected to output a probability score of choosing each action from all possible actions, so that “following the policy” would mean choosing the action with the highest score. In this case, the states were thus embedded as image frame stacks, the actions were the movement of the agent (up,down,right,left) and the rewards were the added game score through an episode, with a policy network whose task was to learn the best actions given state(s) based upon the rewards it achieved in previous episodes.

First, I built a DQN agent from scratch with Tensorflow. Afterwards, I used the Tensorforce library to do the same thing. The reason for using Tensorforce was that its built-in preprocessing and simplicity made the code significantly easier to follow, ensuring that my Tensorflow implementation did not suffer from the kinds of minor bugs that can make the difference between an agent learning or not in RL problems. All games were simulated using OpenAI’s Gym package.

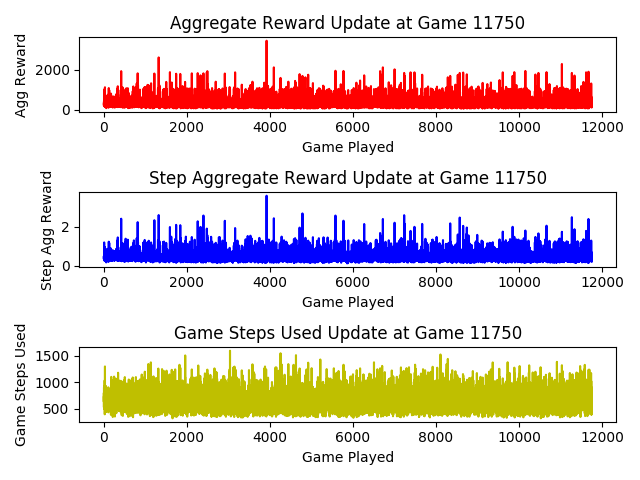

Original Tensorflow Implementation

The pure Tensorflow implementation shows a lot of noise, which is common in RL problems which are extremely sensitive to hyperparameters selected. I chose to have an exponential decay in the value of ε , which is a hyperparameter that determines exploration: with probability ε, the action chosen will be sampled uniformly at random from the action-space, while with probability 1-ε, the action will be determined by the online policy. In the results, though it’s tough to see in the graph, the pure Tensorflow implementation does show some evidence of learning as average returns increased from the completely random policy. This is evidenced by the fact that average returns nearly doubled between the first 100 episodes and the episodes thereafter. After verifying that the other hyperparameters used were consistent with those used in the DeepMind paper, I concluded that either my implementation had a bug or that with the hyperparameters used, a Ms. Pac-Man DQN agent could not become better than what I showed, so I should change them.

It was at this point I decided to verify the experiment with the Tensorforce library, to eliminate the possibility of facing bugs and to facilitate the changing of model hyperparameters far more easily. Eventually, I cut the learning rate in half, expanded the replay memory (from 20,000 to 25,000 experiences), and changed the ε-decay. Cutting the learning rate in general is a good move if your agent is unable to optimize over the policy function because a smaller learning rate enables more sensitive optimization in the parameter space, so that large gradients don’t pass over a desirable local extrema in the function. Expanding the replay memory was kind-of arbitrary- it seemed that the agent did not learn policies that were successful after the beginning of the game, so the intuition was that expanding the replay memory gave the policy increased variance in the states it was trained on and made it more likely to succeed in a larger variety of gameplay scenarios as a result. Lastly (and probably most significantly), I changed the ε-decay because my original implementation I believed could have been mistaken in decaying the ε value too quickly without clipping, which was a mistake. So, I decided to decay it from the original value in the paper and follow the linear-annealment over 1,000,000 episodes to 0.1 from DeepMind’s paper.

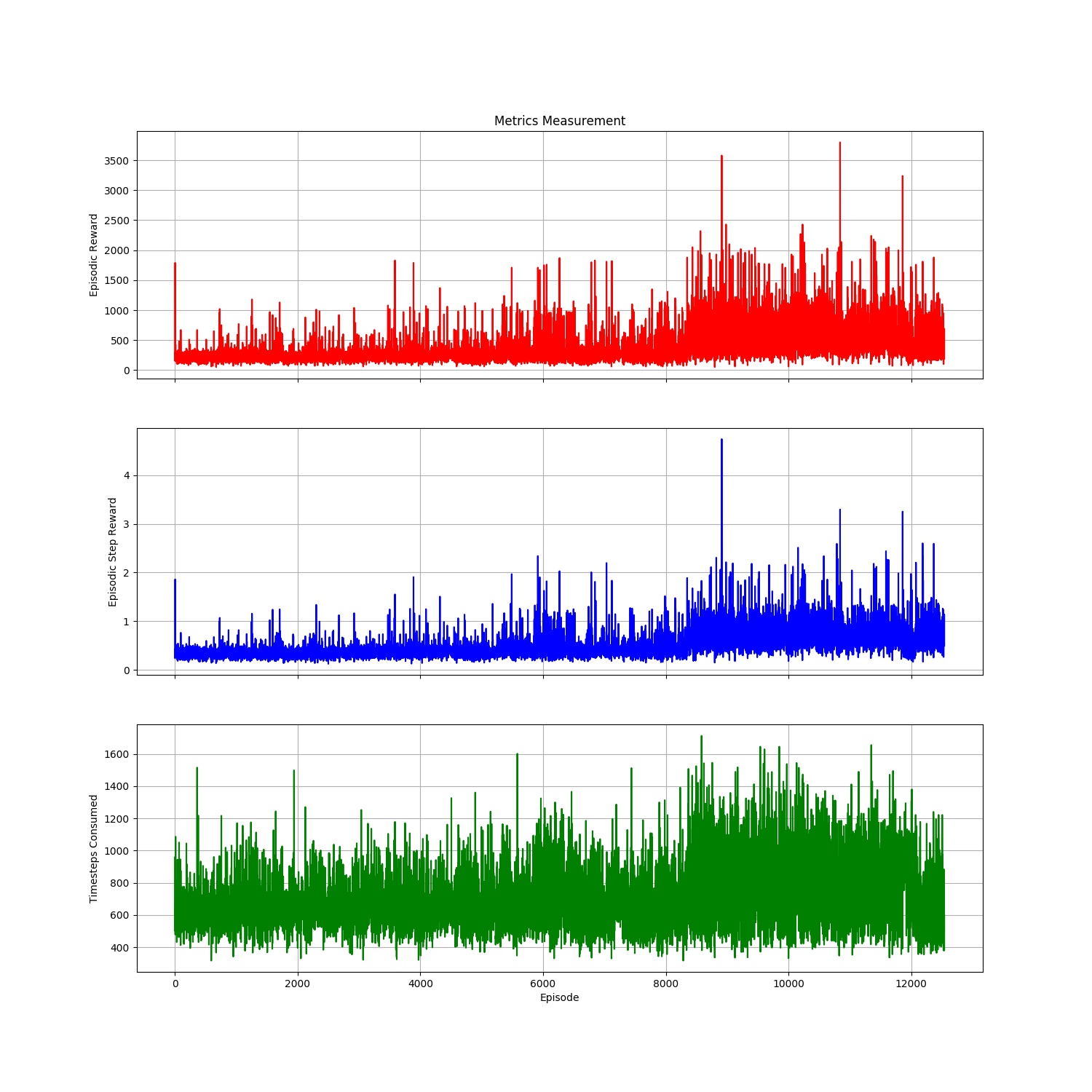

Tensorforce DQN Implementation

This agent shows far better evidence of learning, which means that the first model I made was flawed in its hyperparameter selection. Using Tensorforce, it was easy to compare this with a Proximal-Policy Optimization (PPO) Agent using the same hyperparameters. I did this because PPO is a more popular algorithm in the field today and was easy to implement in Tensorforce.

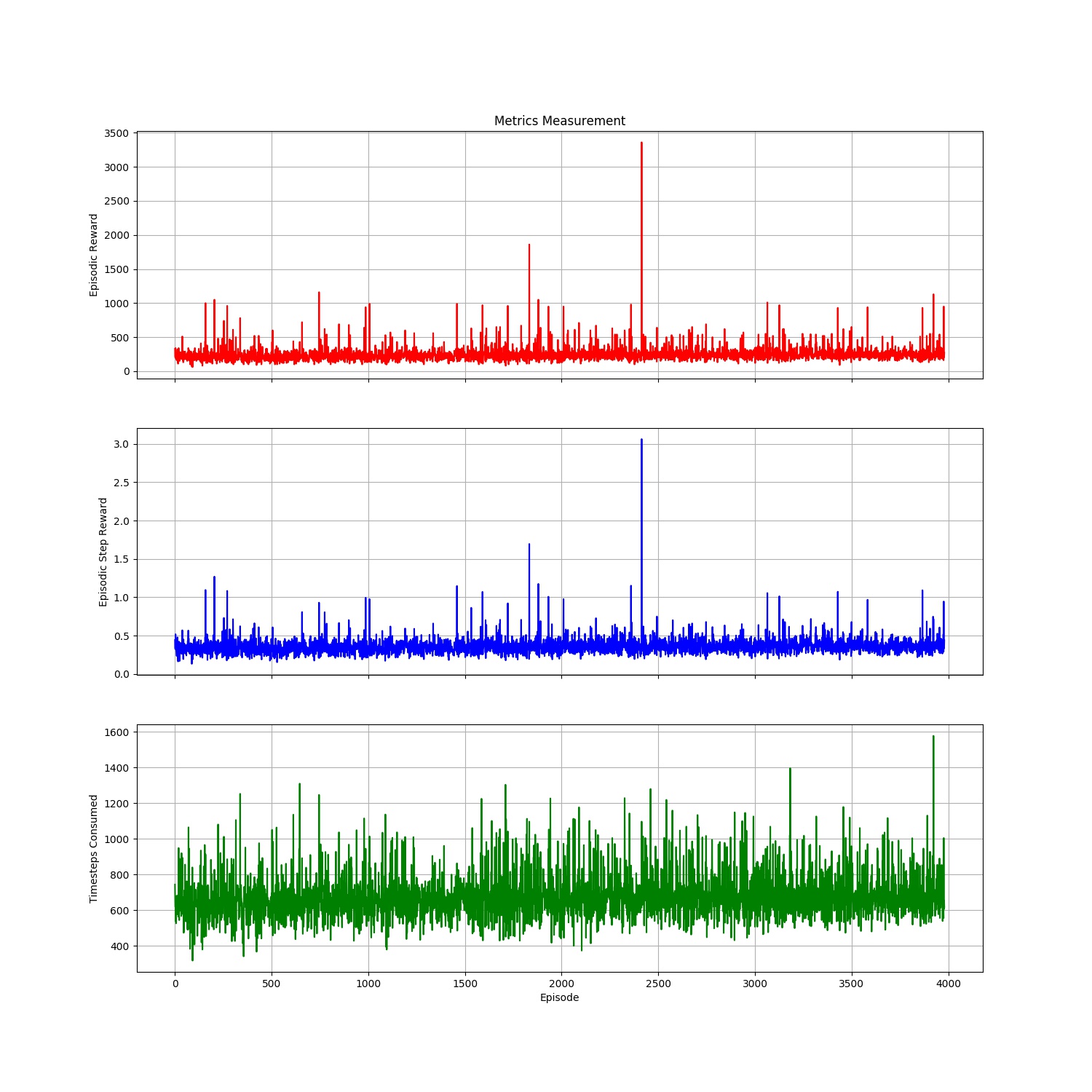

Tensorforce PPO Implementation

Unfortunately, it looks like the PPO agent did not have the ideal set of hyperparameters to learn a useful policy. As RL researchers are well aware, the same hyperparameters don’t work well among different algorithms even for the same problem, underlining the fragility of the algorithms we have today. However, I’d be interested in seeing how a tuned PPO agent performs as compared to a DQN agent for Ms. Pac-Man.

One last point I’d like to talk about is the computational costs of training reinforcement learning agents. For my experiments, the barebones Tensorflow implementation took about 24 hours to run about 12,000 episodes, with no GPU and 8 GB RAM. The Tensorforce DQN took 4 nights on the same machine, and the PPO agent took 1 night to do about 4,000 episodes. Ideally, with the computational resources to train these more quickly using several machines, one would be able to simulate episodes much more quickly and train the models’ neural networks more quickly as well. In advancing the field of reinforcement learning, finding ways to streamline the computational cost of the training (which requires greater processing and memory for simulating environments and training neural networks) is as crucial as the algorithmic progress that has occurred. In that line of thought, one area I’d like to delve into further after this is the various blackbox (gradient-free) methods that exist from previous RL-research. The computational efficiency of these methods might make them a promising method of training along with gradient-based methods like DQNs, policy gradients, etc. In producing a model that is a hybrid of gradient-free and gradient-based methods, one may be able to find quicker convergence, though of course such a hypothesis has little meaning without experimental evidence.