Intro

For most of the past year I’ve been working on a clinical trial for a disease called retinitis pigmentosa (RP) that’s relatively rare, affecting 1 in 4,000 people. Sometimes when I’m asked by friends or family how the treatment works, it’s difficult to describe succinctly, but I’d like to because it’s pretty exciting! If successful, our treatment may be able to restore sight to people with degenerative ocular diseases such as RP, and would be an advancement of gene therapy technology.

The ideas for our treatment were formed by my boss Sheila Nirenberg and her research group. The link contains her TED talk, publications, and news coverage about the research and technology behind the trial. My goal in writing this is to put together some of the things I’ve learned as someone with little biological background, providing a comprehensible and concise overview of the biological concepts underlying the trial.

A Photon’s Journey

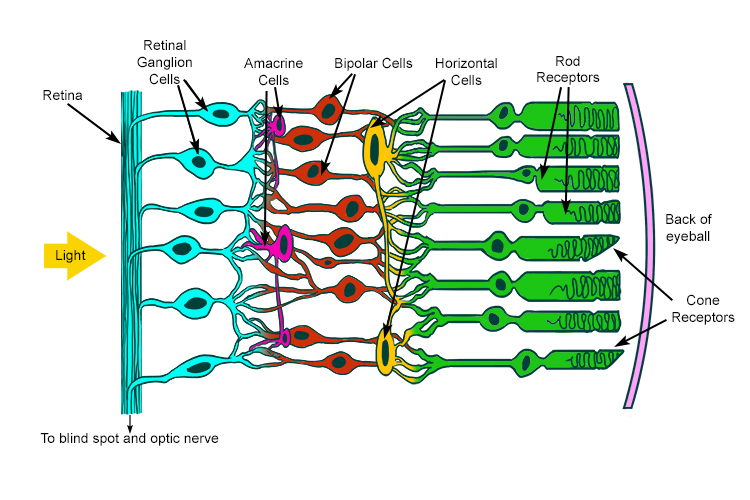

Images that you perceive are formed in your brain based on light entering your eye. After passing through the lens of your eye, photons of light first hit specialized neurons in the retina called photoreceptors, which are subdivided into rods and cones. Photoreceptors generate signals depending on the wavelength and intensity of the light coming in. Rods are mostly found in the periphery of your vision, designed for low-light conditions, and are agnostic to color, which is why you see less color at nighttime. Cones are attuned to colors and are concentrated in the center of your vision, so you see the most detail with them. Light is converted to electrical energy at the photoreceptor level in a process called phototransduction. Phototransduction is a multi-step process, starting with photons hitting a class of proteins in the photoreceptors called “opsins” that contain a substance called retinal. Retinal’s structure changes when hit with photons of a particular wavelength, which begins a series of biochemical processes that result in an electrical potential to be created from the photoreceptors. Light intensity is directly proportional to the number of incident photons, so brighter light leads to a higher likelihood of phototransduction in each photoreceptor. Figure 1 is a good visualization I found for this- one counterintuitive and often confusing detail is that RGCs are closest to the center of the eye and photoreceptors are nearer to the back, meaning light passes through the later layers of the retina prior to encountering photoreceptors.

Figure 1: Rods and cones

Figure 1: Rods and cones

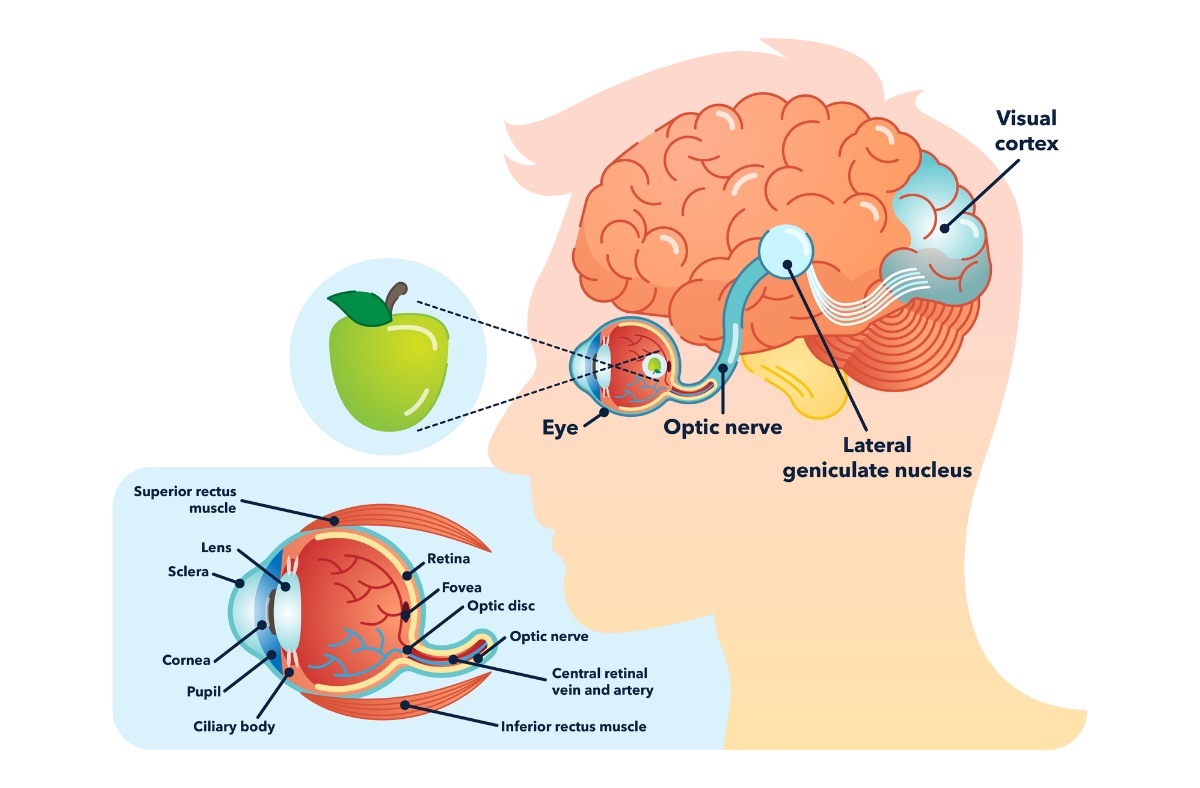

The neural network inside your retina connects these photoreceptors to several intermediate layers of cells which aggregate, filter, and align the signal from the large number of photoreceptors. The transformed signal reaches a final layer called the “retinal ganglion cell” (RGC) layer. Each RGC has a patch of photoreceptors it is connected to via the aforementioned intermediate cells. Different types of RGCs confirm whether the middle of that patch or the surround of that patch are receiving light, and vary by patch size and color. The signal then leaves the retina onto the optic nerve, which transports it to a part of the thalamus of the brain called the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Things get more complicated at the brain, where patches of LGN neurons respond to orientations of ganglion cells. The signal then goes to the back of your brain (occipital lobe) in a place called the visual cortex (aka visual area 1 (V1) aka Brodmann area 17 aka striate cortex). The cortex is a word for the outer part of the cerebrum of the brain, which is the wrinkly looking thing you probably think about when you think of a brain. At this point, you start performing higher-level processing, combining the visual information you’ve received with background knowledge to recognize, associate, or trigger reactions to what you’re seeing, which happens in various other parts of the brain in ways that are yet to be fully understood.

Figure 2: The visual pathway

Neurons

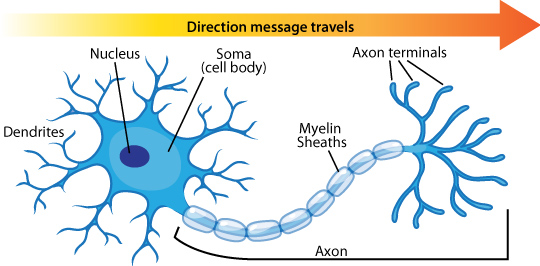

When I say something is “responding” or “activating”, it might be unclear what that means. The basic unit of neural function is a cell called the neuron, and most neurons, given the desired input, can “fire” an action potential- this is the “response” or “activation”. Action potentials are events where the neurons undergo a large voltage increase from their resting state, which can be transmitted out of the neuron through a wire-like structure called an axon. Signals from other neurons are collected by other wire-like structures called dendrites: each neuron has many dendrites but one axon. In most neural pathways, axons meet with dendrites at places called synapses, which are structures regulating the passage of signal between a presynaptic and postsynaptic neuron via chemical or electrical means. The 14-16 billion neurons each can synapse with a large number of other neurons, which enables your brain to function in all the ways it does! It’s also interesting to recognize that neural action potential firing doesn’t change in amplitude- no matter what the input signal or stimulus is, the output action potential usually has about the same amplitude. Instead, the rate at which action potentials happen is indicative of the neuron’s response, so the rate is what matters to the neural network in most cases, not the amplitude.

Electrical activity in neural networks is caused by potential differences across membranes. Ionic gates (gates that let out or let in a specific ion, like Na+) in the membrane control the potential across the membrane, and these potential differences move down the axon to synapses. This traveling electrical signal is processed by other neurons, and can lead to neutotransmitter release and other biochemical reactions.

Figure 3: The visual pathway

Figure 3: The visual pathway

Optogenetics

What would happen if some portion of a neural network stopped working? This may be harmful to the function of that network, whatever that might be. Neural networks exhibit both redundancy (multiple neurons serving the same function) and plasticity (networks being able to learn and adapt to changes) so it’s not likely that things would go wrong, if, say, 10 individual neurons got destroyed. But if some disease destroyed an entire class of neurons, or an entire portion of a neural process- this could be problematic. To fully replace the missing neurons, you’d need to know the signal transformations they perform. If the neurons are not missing altogether but simply weaker, it may be sufficient to merely amplify the signal. Whichever path you take, you want to alter the damaged signal from only a selected group of cells, while leaving the healthy signal from other cells intact.

Optogenetics is a promising answer that plays well within these constraints. At the highest level, a neuron that previously was not firing creates new ionic gates which are responsive to external light. This development occurs because the neuron is expressing a gene brought to it by a viral vector (not one that self-replicates, just a carrier that inserts genetic information into the neutron). The genetic information and physical viral dynamics can be used to specify which kinds of neurons get infected. Once infected, a light of a particular wavelength can open and close more of the gates that determine membrane voltage, thereby triggering action potentials that weren’t being produced before. This is an improvement over, say, an array of electrodes because it offers a much more precise delivery that doesn’t require a permanent invasive apparatus.

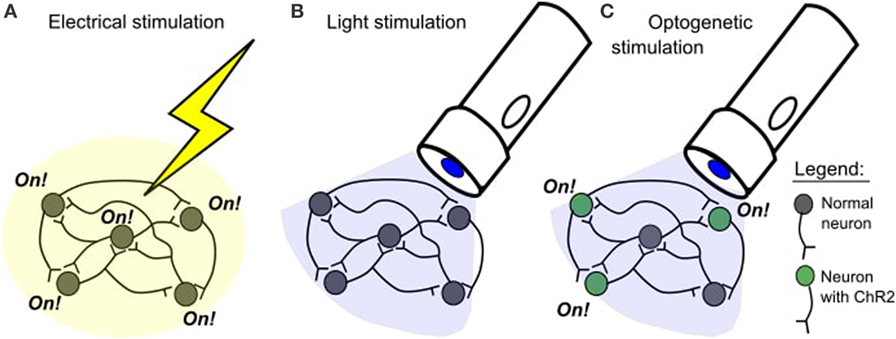

Figure 4: An overview of optogenetics. ChR2 is an example of one type of opsin.

Figure 4: An overview of optogenetics. ChR2 is an example of one type of opsin.

Tying it together

In degenerative diseases like RP, the photoreceptors aren’t sending any signal to the other parts of the retina, so the RGC layer isn’t receiving any information to work off of. An optogenetic approach allows the RGCs to produce their own opsins, making the RGC layer respond to light instead of the dysfunctional photoreceptors. This leaves a problem: what happens to those intermediate transformations? If we show the same image to the RGCs that the photoreceptors normally get, there’s no guarantee it’ll be meaningful to the RGCs- otherwise, the healthy retina wouldn’t really have needed the layering it has to begin with. Ideally, we should to present the RGCs with an encoded image instead, one that carries the information from the original image along with the transformations provided in the intermediate layers.

Bionic Sight’s technology is able to do that because we can use a proprietary neural coding algorithm to transform the image for the RGCs and deliver it via the optogenetic procedure. In this way, an input image can bypass the retina given healthy RGCs and everything after.

Image credits

Post Main Image: The Scientist Magazine

Thumbnail Background Image: Columbia Medicine Magazine

Figure 1: Mammoth Memmory

Figure 2: Perkins School for the Blind

Figure 3: Arizona State University

Figure 4: Frontiers for Young Minds